Public finance management (PFM) is one of the catchphrases that dominate conversations on the economy and government funds in general.

It is one area where politicians from both sides of the divide pledge to improve in a bid to make things work.

It is little wonder, therefore, that the Malawi Government and its development partners invest their energy and resources to ensure a vibrant PFM.

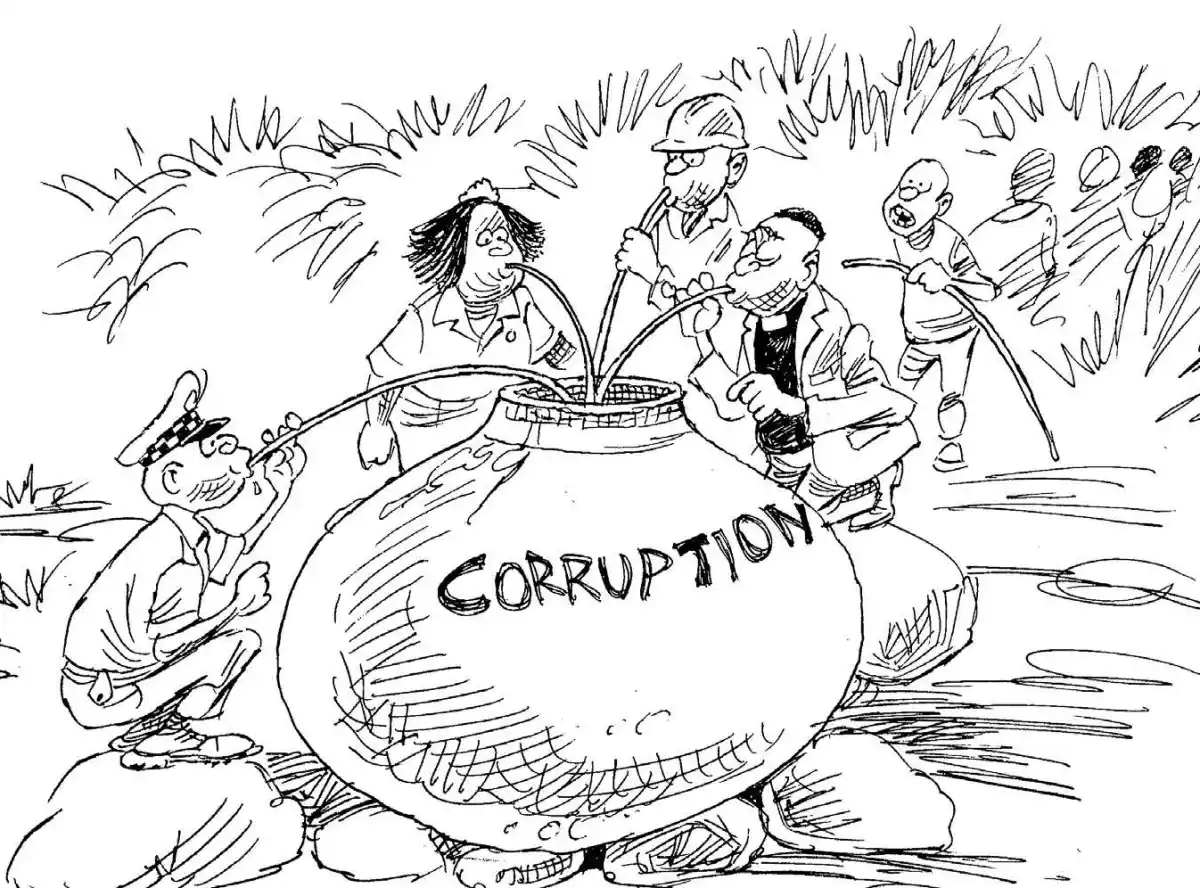

Where the PFM is ignored or compromised, public resources are abused and the results are often detrimental to the economy as we saw in 2013 when Cashgate, the plunder of public coffers through dubious payments, inflated invoices and goods or services not rendered, was exposed.

Transparency International Knowledge Hub defines PFM as a central element of a functioning administration, underlying all government activities and encompassing the mechanisms through which public resources are collected, allocated, spent and accounted for. I quote “a central element of a functioning administration”. End of quote.

PFM systems emphasise accountability and adherence to systems to ensure that every tambala spent is accounted for and used for the intended purpose.

Ideally, PFM reflects “a functioning administration”. This is why I have found disturbing some newspaper headlines that send a picture that our systems do not seem to be working as efficiently as they should be.

These headlines quoting reports from reputable institutions such as the African Development Bank (AfDB) and the World Bank should be considered as red flags and push those entrusted with management of public resources into action.

One of the headlines in Business News section of The Nation published last week screamed ‘World Bank notices public finance gaps’. This one came after a more “brutal” one that read ‘Public purse still leaking—AfDB’.

Briefly, the World Bank said our economic and public finance management remains poor as evidenced by failure of economic policies to reduce poverty and promote sustainable growth, among others.

It said the country’s PFM was rated low, largely due to disjointed management of arrears, continued corruption and slow progress in enforcing procurement and audit systems.

The AfDB, on the other hand, said in its report in May that despite strengthening the PFM law, leakages persist in Malawi’s public purse. This puts the credibility of the PFM policies at stake.

What is frustrating to many a patriot is that these gaps come on the back of the Malawi Government taking steps to improve public finance management, including adoption of the new PFM Act in March 2022.

PFM is key to attracting foreign direct investment and achieving national development at large through good economic policies that can reduce poverty, promote sustainable growth and effective use of development assistance. No investor would want to put their money where corruption is rampant, where the systems are “broken” down. It is critical to improving a country’s risk rating too.

Fiscal discipline is yet another important element in PFM, but in an election year the Executive appears to be in overdrive to spend to win voters’ hearts. Nothing wrong with enticing voters, but where the source of financing is borrowing it becomes a matter of concern given the ever-rising public debt stock that is becoming unsustainable.

Slips in the implementation of PFM reflect a failure to enforce laws and ensure that government ministries, departments and agencies (MDAs) are adhering to laid down systems and procedures to seal the loopholes.

It would be gross negligence for a country banking on the goodwill of donors to ease its debt burden and rejuvenate the economy to throw all caution to the wind as PFM is a critical condition demanded by development partners, including the International Monetary Fund.

The weak internal controls should be revisited and improved on to ensure MDAs play by the rules.

My observation over the years has been that the auditors’ recommendations and concerns have always been the same for the past decade, what has lacked is the political-will to implement the changes.

In the run up to the court-sanctioned fresh presidential election held on June 23 2020, President Lazarus Chakwera and his Tonse Alliance partners passionately campaigned on a platform of doing “business unusual” to restore “broken systems” that reduced the PFM system to a “leaking bucket”.

Doing business unusual entails taking to book controlling officers who preside over abuse of resources as provided by law.

It also means acting on recommendations by oversight institutions, including parliamentary committees on sealing loopholes.

To me, the gaps are certainly not about the lack of an enabling law as it was recently amended

0 Comments