When Israel was in Egypt’s land, let my people go! … Go down, Moses, way down in Egypt’s land, tell old Pharaoh to let my people go…” – part of an African American spiritual

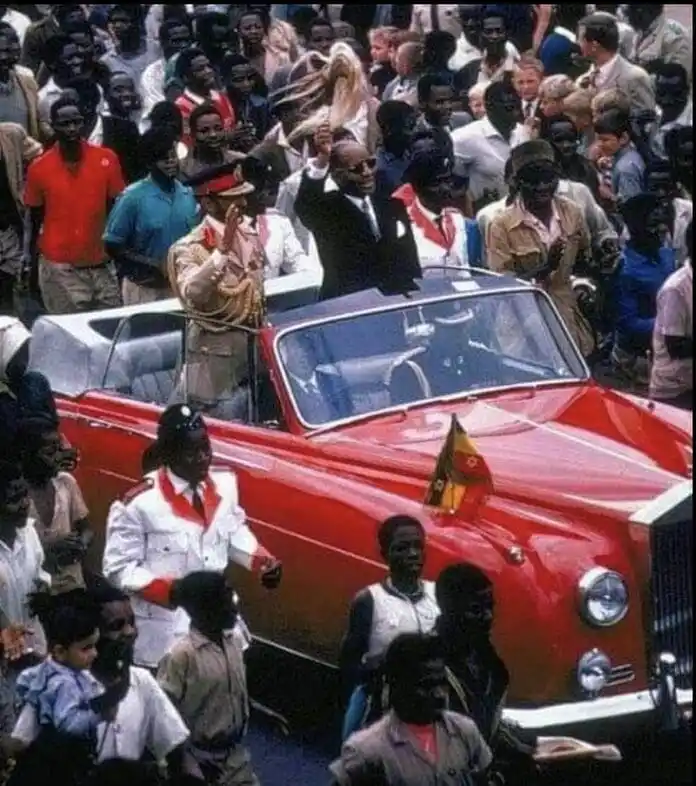

Sixty years ago on July 6, 1964, the former protectorate of Nyasaland became independent from British rule, and changed its name to Malawi. Two years later in 1966 on the same date Malawi became a Republic with the then Prime Minister, Dr. H. Kamuzu Banda becoming President. Happy 60th anniversary to all Malawians. It has been a long and sometimes hard and bitter journey; I trust we are all proud to be Malawians. I am proud of my Malawi roots.

Today I came to tell you that I was in the room and as sad, upsetting and infuriating as recent events have been, there have been others in one party rule as well as multi party rule. More light will be shared on this.

1. Kamuzu – black man to fight white leaders – From 1958 to 1964, a man called Dr. Hastings Kamuzu Banda landed in Malawi (on July 6, 1958), fighting the white colonial rulers. Many rallies were held; for some reason my mum and dad were very connected with this fearless person. My Dad was Kamuzu’s first interpreter; my Mom the hostess to the many political officials and friends that gathered for the rallies that were fighting the British. They formed a political party called the Nyasaland African Congress (NAF). I was in the Room of History here.

2. In 1959, Kamuzu had caused so much trouble, the British government declared a State of emergency and Kamuzu was imprisoned. While he was still at the Chichiri Central Prisons, my dad and some members of the NAC surrendered themselves, declaring that they too were part of the trouble Kamuzu was causing that led him to be imprisoned. No problem here. The group was put in jail. The two groups were taken to Rhodesia but separated between Gwero and Khami. I was in the Room of History here.

3. They were released in 1960; the British governors negotiated with the Home office to engage in talks with Banda. Being the eloquent talker, filled with knowledge of ancient, biblical and modern history, Banda convinced the colonial office to free Malawi from them. Malawi followed a group of other independent negotiators at Lancaster House: among these were Ghana, Kenya, Somalia, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Tanganyika (united with Zanzibar to become Tanzania), Uganda, The Gambia, Botswana, Zambia, and Rhodesia (Ruled by Ian smith and later became Zimbabwe with Robert Mugabe as leader).

4. After his release from prison and his successful negotiations that won Nyasalance freedom from the British, women, led by Mrs. Rose Chibambo, arranged women in Blantyre to perform traditional dances to celebrate Kamuzu. I was in the Room of History here. As a student of Blantyre’s leading girl’s school (also known as Blantyre Girls’ School), we went and danced for Kamuzu. I remember so many girls introducing great traditional songs they dance in their villages. These were turned into praise songs by the women. As a thank you to the women and girls, Kamuzu ordered a pair of Pata-Pata shoes for all the dancers. My very first pair and I wore them with pride. This was in 1963.

5. I rewind to 1962 when the first two of so many other suspicious accidents took place in a spate of six months. The first was of Lewis Somanje Makata, a very jovial Ndirande icon. In March, the car he was driving collided with another car on the Mchinji Road as he was travelling on a mission Kamuzu had sent him. Six months later in September, Dunduzu Chisiza Sr.’s car was found with his mangled body under the Thondwe Bridge as he was coming to Blantyre. Even though I was a young girl, the talk by adults about these two deaths angers me to this day. As with many of such incidents, the people’s anger reaches fire-hot intensity because I, like many Malawians, never know to whom to direct the anger. I was in the Room of History here.

6. In 1963 my dad, along with Bridger Katenga, Tim Mangwazu, Vincent Gondwe and David Rubadhri were sent to London School of Economics for training. While there, these became Malawi’s first ambassadors and high commissioners to various countries (Great Britain – later became the United Kingdom, US, UN, Kenya, Ethiopia, and Ghana). Their postings started in 1963 and families joined their fathers/husbands the following year. The first independence celebrations I spent was in the UK where dad was the High Commissioner. The biggest cultural shock was to see my mom and dad sitting next to the leaders (prime ministers and even the Queen and Duke of Edinburgh). As children we feared white people; their children called us monkeys and spat at us while riding on their horses in Ndirande. In faraway England, we were friends with the white people.

7. My biggest moment in my three and half year stay in the UK was meeting Kamuzu, at close range for the first time. I was sickly and had swollen legs, joint pains; so I could not give the kugwada (courtesy) bit when greeting the Prime Minister. He asked if he could examine me (Dr. H. Kamuzu Banda was a medical doctor before he came into politics), and my mom and dad agreed. Within minutes. He diagnosed my ailment as Rheumatic fever; they were advised to take me to Dr. Sam Bhima, a Malawian doctor practicing in the UK.

8. In 1965, Malawi had its first upheaval when a major part of Banda’s cabinet in misunderstandings, among them the introduction of a small charge for medical treatment, led to ministers regretting having called Dr. Banda from Ghana to help them in the fight for freedom. The first exodus of the truckload of ministers and many others known as the 1965 Cabinet Crisis shook the country. The Prime Minister recalled his ambassadors for consultations. Of the first five first ambassadors, three chose to remain in service Katenga, Mangwazu, and Mbekeani). This choice, as was for the other ministers that chose to remain in Malawi, did so on the understanding that they were to work with Kamuzu and make delivery on his vision for the country. While the cabinet ministers and others labeled the remaining officials as “stooges,” the massive development work both in Malawi and on the international platform, led to the transformation Malawi was privileged to be witness to. I was in the Room of History here.

9. The years of 1966 to 1971 were the growth years whereby Kamuzu introduced and reiterated his Gwero dreams. There were three: The capital moved from Zomba to Lilongwe, University moved from Blantyre to Zomba, and the Lake Shore Road linking the south, centre and northern regions. Malawi also witnessed an agricultural revolution of sorts: the spreading of ADMARC in all the regions and districts, to buy farmers’ produce; establishment of feeder corporations such as cloth manufacturing industries (cotton farming, cotton ginnery, tailoring), rice farming. While some were managed under the Press Corporation, others were by Lonrho (London-Rhodesia – the giant corporation owned by Kamuzu’s friend Tiny Lowland). Kamuzu encouraged his ministers to buy and operate farms. On another level, the country, with help from Israel and Taiwan (known as the Republic of China until 1971).

10. Many of the visions Kamuzu had were realized by establishing friendships with countries that were shunned by other African countries. Countries such as Apartheid South Africa – they helped in the move of the capital to Lilongwe; the Taiwanese helped in Malawi Young Pioneer training of youth and establishing irrigation schemes in the rural areas, and Israel (whom Malawi supported in the Israeli Egypt Six Day War). And the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) – countries such as the US, UK, France, Germany, Italy, and others; these poured in millions of dollars in development aid, leading to the massive 30-year mushrooming of labor-intensive establishment of companies in Malawi. I was in the Room of History here.

One main ingredient that is seldom mentioned: Banda hated communism and often ridiculed the notion of working hard in your field and what you gain from selling your produce, you give to the state to redistribute the others. This anti-communism position won Banda the hearts of many capitalist countries.

All he had to do was cough, and streams of monies came pouring in; much, much money sometimes fighting each other.

This joyride existed until 1991; the year and others to follow were the years of a rude awakening and bitter separation.

0 Comments